Don’t asset strip your business schools, universities are warned

Business schools often are seen as a “golden goose” as their profitable revenues cross-subsidise other research-intensive faculties, Robert MacIntosh, chairman of the Chartered Association of Business Schools and pro vice-chancellor of the business faculty at Northumbria University, has warned.

He also said that the drop-off in international student numbers was affecting business schools. He argued that with universities also grappling with rising costs and falling real-terms income from domestic students, there was a real risk that business schools would not receive the investment they needed.

“Business schools are, by and large, profitable, so there is definitely a golden goose thing,” he said. “While those surpluses are generated, in any other line of business you would look to reinvest to keep the offer competitive and to keep the student experience a high-quality one. There is a bit of a concern that we don’t asset-strip our business schools or deny them the opportunity to reinvest and grow.”

MacIntosh said he had not yet seen university vice-chancellors protect the budgets of other subjects over business, but the risk remained. “Business schools are often handing over to the parent university tens of millions of pounds of surplus income that cross-subsidises all the professional services, support, library and lots of other disciplines,” he said, “so when business schools encounter financial challenge, as they are doing because of a drop-off in international students, parent universities catch a cold really quickly.”

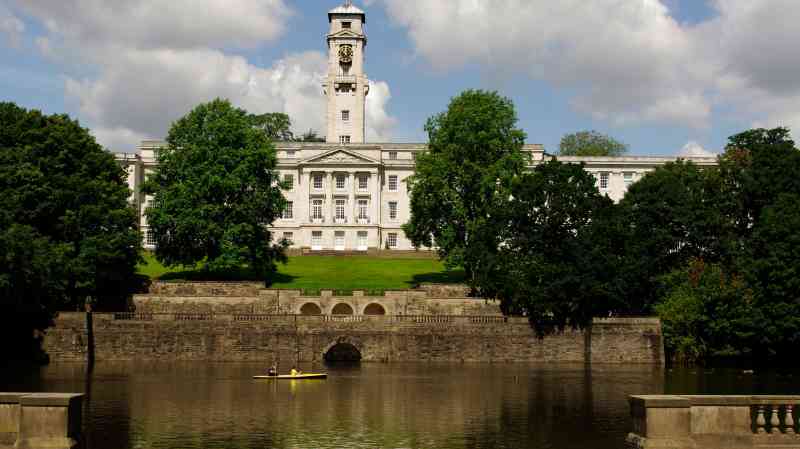

More than 50 universities have announced redundancies, including in recent months at Aston, Cardiff, Nottingham and Hull. Many are on to their third or fourth round of cuts. In May, the Office for Students, an industry regulator, said that 40 per cent of all universities in England expected to be in the red this year.

MacIntosh is in the process of moving from Northumbria to the University of the West of Scotland to take up the role of pro-vice-chancellor for research and innovation. He is not alone. Times Higher Education reported in July that at least one in five UK universities was changing their vice-chancellor or faculty leadership this year.

MacIntosh said he had spoken to a wide range of business school leaders and that the financial picture was mixed, with “lots of quite big and quite well-known universities seeing a significant drop in international student recruitment. But some are seeing an increase.”

The business schools of large universities can take in 2,000 to 3,000 international undergraduate students a year, he said, each paying fees of about £22,200 per year, compared with £9,250 for domestic students in England and Wales and £4,750 in Northern Ireland. The strain on business schools was expected to continue in this academic year, he added.

MacIntosh has held senior leadership roles at the business schools at Heriot-Watt, Glasgow, and Strathclyde and said he saw the role of business schools as the “front door” for local businesses to the whole of the university.

“There is this unfortunate assumption that [business schools] means large, corporate private sector engagement as our target audience,” he said, highlighting that MBA students represent only 8 per cent of the total in a typical business school. “We do huge amounts of work with start-ups, small businesses, with charities and public organisations.

“But businesses are not always inclined to knock on the door of a university. They are much more inclined to knock on the door of a business school, which sounds like a safe space for them.

“It might then prompt a conversation about a chemical engineering or a bioengineering or an actuarial maths problem where we can connect you to the right people.”

MacIntosh encouraged small business owners to participate in the government-backed “Help to Grow” management training scheme, which provides 50 hours of structured learning, as well as access to mentors, for £750.

The scheme, launched by Rishi Sunak, is funded until next April and has been taken up by more than 7,000 businesses. “There is a huge opportunity if you haven’t participated in that programme,” he said. “It is still in place and it has survived the change of government.”

MacIntosh said the new government should include post-graduate training in its planned reforms of the apprenticeship levy. Employers were stopped from using the levy to pay for middle and senior management to update their skills in 2018. The view was that large, private companies were overusing the scheme, but MacIntosh said it was also popular with the NHS and other public sector organisations.

“They were upskilling themselves through that process,” he said. “If I was in business, I would be saying to my elected representative, ‘Why are you so against the idea that I could get some post-graduate level apprentice provision for my leadership team, given I am paying into a levy that I am not finding it easy to use?’ ”

Post Comment